Detail of ceiling by Geoffrey Preston for a hunting lodge in Dorset (2016)

My interpretation of a raffle leaf, modelled in clay and cast in plaster (2010)

Crockets at Exeter Cathedral (1981)

Decoration was a dirty word when I was a student. It took a time to get over the brainwashing that surface decoration was bad and the Puritan 'truth to material' mantra, and really learn my craft and find my place in tradition and to start to enjoy modelling.

The forms of crockets and raffle leaves are the building blocks of my work. Working as a carver at Exeter Cathedral I met my first crocket and later, at Uppark House, I had the good fortune to model a lot of raffle leaves in that exceptional medium of stucco. Crockets are leaves carved in profile on the arches and pinnacles of medieval buildings. Raffle leaves are the characteristic leaves of rococo art. There has always seemed to me to be a similarity and a continuity between the design and modelling of the two forms. Artists often look back and take the best of what was done before and carry it forward.

What does the crocket do? At least part of the answer is indicating that nature is part of the architecture and enlivens its static form. It creates a flow of natural form over the architecture. Adding complexity. Adding vibration. The 13th & 14th century crocket is a sculptural statement.

Crockets at Exeter Cathedral (1981)

There's everything here to be learnt about modelled form. For whether the crocket is carved in wood or stone it clearly began as a clay model which the carver copied. Look at the way volume is treated. Convex surfaces mostly, maybe 75% convex. That fullness is what's visually satisfying and it echoes the fretted outline, the C and S shapes of the ‘linear’ composition.

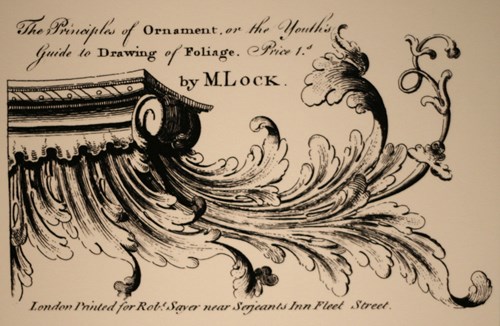

The raffle leaf is one of the fundamentals of 18th century decoration. It is a graceful, acanthus type leaf with the S shape of Hogarth's Line of Beauty. It has a convention of form that develops as a progression from its beginning point, dividing by twos and threes and sub-dividing again and maybe turning over itself as if moved by wind or water. To me, they have the same feeling as copper-plate handwriting; flowing, harmonious but active and legible - as illustrated so beautifully in George Bickham’s The Universal Penman.

Beautifully illustrated raffle leaf by Matthias Lock, from the frontispiece of The Principles of Ornament, c.1765 (© Metropolitan Museum of Art)

These long, curling leaf forms abound in rococo decoration. I think they have a lot in common with the crocket: C shapes; S shapes; mostly convex in volume; gestural. In hand-modelled plasterwork, particular variations are almost like signatures, associated with modellers like the Artari or the Franchini families. These dynamic, elegant forms are all about the modelling; here modelling reaches a summit of harmony and inventiveness. A tour de force. A symphony of curves. Pure sculptural joy.

My work is modelling clay. Soft clay. Experienced fingers moving the pliant, receptive, elemental clay. Forming. Putting my intentions and feelings into my fingers makes form appear... I'll modify it with tools. Mostly I work in relief with a clay background - 2 dimensions; then bring the form out into the 3rd dimension, or push it back a bit. Experience gives you freedom with your medium. Gesture is important; controlled, intentional, but free, too. What gestures are possible? C shapes and S shapes. Curves defining and creating form, adding the clay, pushing and pulling, the gestures composing, harmonising. There's something in this fluid process that's natural, instinctive. Like the way nature works, like waves and wind and cloud. Yes, it does feel romantic.

A detail of a ceiling I designed for a hunting lodge in Dorset (2016)

I like to use these forms as freely as I can. Making use of them quite extravagantly, allowing shapes and modelled themes to occur that cannot be planned in the drawing. In fact you are drawing in the clay. The pencil drawing gets you into the right place with your design, proportion and meaning then comes the liberation of working in the clay and realising the new, and somehow unimagined possibilities of your medium.

Here’s a poem by D.H. Lawrence. It’s a slight tangent from what I’ve been writing about, but one I think Artworkers may appreciate:

'Things men have made with wakened hands, and put soft life into

are awake through years with transferred touch, and go on glowing

for long years.

And for this reason, some old things are lovely

warm still with the life of forgotten men who made them.'

Things Men Have Made, DH Lawrence (1929)

Stucco in the church of Maria Steinbach, Bavaria (1746)

Posted on: 09 July 2020